Data Science

Machine learning & data science for beginners and experts alike.- Community

- :

- Community

- :

- Learn

- :

- Blogs

- :

- Data Science

- :

- How Concerned Should You be About Predictor Collin...

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Notify Moderator

This past Northern Hemisphere summer I gave several talks (some in the Southern Hemisphere) in which one of the Q&A topics was the problem of collinearity between predictor variables (also known as multicollinearity). My stock response to a question on this topic was (and is) to reply with the clarifying question “How many rows do you have to develop the model?” If the follow-up response was in the tens of thousands, my counter response was “Don't worry about collinearity.” In contrast, if the audience member's response was a few hundred rows or less, my response was “Very!”

While these two different responses may seem contradictory, they actually are not. I've found that many people who build predictive models know from the instruction they have received that predictor collinearity is “bad”, but they often don't have the intuition behind why it is bad, and when it will be relatively more or less bad. The goal of this post is to provide you with some intuition behind the problems associated with predictor collinearity, and provide some rules of thumb about when, and when not, to be concerned.

The Intuition Behind the Effect of Collinearity

In a model with only two continuous predictor variables, the Pearson correlation between the two predictor variables is an excellent measure of their collinearity. The value of the Pearson correlation between the two predictors is an indication of the relative overlap of the information that the two variables provide, as the overlap in the information provided by the two predictors increases, the amount of information specific to each predictor decreases. This overlap in the information between the two predictors means that the amount of information specific to each of these two predictors that each row of the data provides is reduced. Put another way, collinearity reduces the information content of each row of data with respect to the effect each of the two predictors has on the target, and the more collinear the predictors are (the higher their Pearson correlation), the more the information content of each row of data is reduced.

I started with the two continuous predictor variable case since it is the easiest one to think about. However, the reduction in the effective information content of a row data caused by collinearity generalizes to more than two predictor variables, and to both continuous and categorical predictors.

The reduction in the effective information content of a row of data means that the precision with which we are able to determine the effect of a predictor variable on the target is reduced. In the context of a traditional linear regression model, what this means is that the uncertainty around the value of a regression coefficient increases with the level of collinearity. In a linear regression model, the uncertainty about a coefficient estimate is captured by its standard error. As a result, an increase in collinearity between two predictors increases the standard errors associated with the coefficient estimates for those two predictors. This increase in the standard errors caused by collinearity is known as bias. One important point, that is often not completely understood, is that the effect of collinearity results in a bias in the estimate of the standard error of a coefficient, but does not result in a bias in the estimated coefficient itself, which turns out to be important. As a result, the main effect of collinearity in the case of a traditional regression model is to make tests of whether a particular coefficient is different from zero (via a t-test for a linear regression model, or a z-test for a generalized linear model, such as logistic regression) to be overly conservative (i.e., it makes it more likely that a coefficient will be deemed statistically insignificant).

Since the effect of collinearity is to reduce the information content of a row data (reducing the precision with which we can determine the effect of a predictor), but does not bias the measurement of a predictor's effect, it means that we can achieve an acceptable level of precision in our estimate of a predictor's effect by increasing the number of rows of data used to estimate the model. This is the reason behind my advice on how concerned you should be about collinearity depends on the number of rows of data available to develop a model.

An Example to Illustrate the Effects of Collinearity

This illustration is based on a case where y is the target variable, and there are three predictor variables (x1, x2, and x3). The true relationship between the target and the predictors is given by

y = 0.5 - x1 + x2 + 1.5(x3) + e,

where e is a normally distributed random value with a mean of zero and a variance of one. The values of x1, x2, and x3 are draws from a multivariate normal distribution, in which all three have a mean of zero. To examine the effect of collinearity, what varies in the analyses is the correlation between the three predictor variables, and the number of rows of data available to estimate the model. With respect to the correlation between the predictors, we look at there different cases:

- No collinearity: All three variables have a correlation of zero (the case of no collinearity)

- Moderate collinearity: The correlation between x1 and x2 is 0.5, and both x1 and x2 have a correlation of 0.15 with x3

- High collinearity: The correlation between x1 and x2 is 0.99 (the case where they are nearly perfectly collinear), and both x1 and x2 have a correlation of 0.3 with x3

This case corresponds to a traditional linear regression model of the form

y = b0 + b1(x1) + b2(x2) + b3(x3) + error,

where b0, b1, b2, and b3 are the model coefficients to be estimated using linear regression, and error is the normally distributed error term of the model. The effect of x1 on y is captured by b1, and it is the ability to estimate this relationship which I focus on in the analysis that follows (the effects of the other two predictors follow similar patterns). In the case of x1, the estimated value of b1 should be near -1.

In all the analyses cases, what is examined is the empirical distribution of the estimated values of b1 across 1000 simulated data sets. This setup allows the analysis to be shown using a series of histograms.

The first analysis examines the ability to estimate b1 precisely under the three collinearity cases when only 50 rows of data are available for the analysis. This may seem like an unusually limited amount of data, but it is a much more common use case than one might expect. It is very common when working with monthly time series data (e.g., the monthly sales of a particular product over the last four years, resulting in a total of 48 rows of data) and in experimental data (e.g., a 50 subject neuroscience experiment based on MRI images). The results of the first analysis are shown in Figure 1.

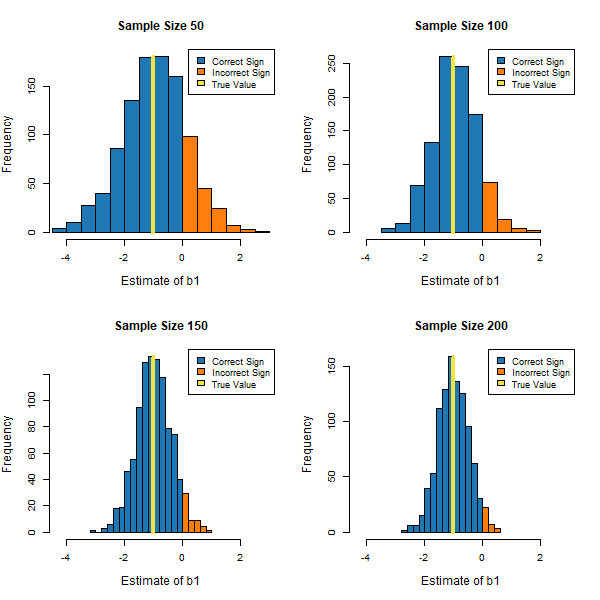

The next analysis examines how adding additional rows of data (increasing the estimation sample size) helps to improves our ability to precisely estimate the effect of x1 on the target in the case of high collinearity, since this corresponds to the case where collinearity has a truly significant impact on precision). Figure 2 show the results of this analysis based on four different levels of available data: 50 rows (as in the last analysis), 100 rows, 150 rows, and 250 rows of data.

“Rules of Thumb” Based on the Analysis

There are two important takeaways from the analysis in this post that should help in determining how concerned you should be about collinear predictor variables. First, the effect of moderate levels of collinearity on the precision with which the effects of a predictor variable on a target can be estimated is fairly minimal, but the level of precision degrades substantially as the level of collinearity becomes very high. As a result, there is a need to be very concerned about high levels of collinearity, but not about moderate or low levels of collinearity. Second, even in the presence of high collinearity, acceptable levels of precision in determining the effect of predictors on the target can be achieved if there is a sufficient number of rows of data available to estimate a model. Put another way, if there is a lot of data (several thousand rows of data or more), even high levels of collinearity do not pose a major problem.

To sum it all up, if the collinearity between the variables is nonexistent to moderate, there is basically no need to be concerned about it. There is also basically no need to be concerned about collinearity if the numbers of rows available to estimate a model exceeds several thousand. The case where there is a real need to be concerned about collinearity is when the level of collinearity is high, and there are fewer than a few thousand rows for estimating a model. This becomes particularly true when there are a few hundred or fewer records available for model building.

Chief Scientist

Dr. Dan Putler is the Chief Scientist at Alteryx, where he is responsible for developing and implementing the product road map for predictive analytics. He has over 30 years of experience in developing predictive analytics models for companies and organizations that cover a large number of industry verticals, ranging from the performing arts to B2B financial services. He is co-author of the book, “Customer and Business Analytics: Applied Data Mining for Business Decision Making Using R”, which is published by Chapman and Hall/CRC Press. Prior to joining Alteryx, Dan was a professor of marketing and marketing research at the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business and Purdue University’s Krannert School of Management.

Dr. Dan Putler is the Chief Scientist at Alteryx, where he is responsible for developing and implementing the product road map for predictive analytics. He has over 30 years of experience in developing predictive analytics models for companies and organizations that cover a large number of industry verticals, ranging from the performing arts to B2B financial services. He is co-author of the book, “Customer and Business Analytics: Applied Data Mining for Business Decision Making Using R”, which is published by Chapman and Hall/CRC Press. Prior to joining Alteryx, Dan was a professor of marketing and marketing research at the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business and Purdue University’s Krannert School of Management.

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.